The Asian Pacific American Medical Students Association (APAMSA) is a national organization of medical and pre-medical students dedicated to addressing issues and health challenges that affect the Asian, Asian American and Pacific Islander American communities.

Penn State College of Medicine’s APAMSA chapter strives to bring together students who are interested in advocating for the health and well-being of the Asian and Asian American communities. It also serves as venue for medical students to network and assist to advance diversity and inclusion efforts.

Leadership

Jump to topic

Search

Students Share Their Heritage

In honor of Asian and Pacific Islander American Heritage Month in May 2020, the APAMSA board created a “My Asian Heritage” newsletter showcasing the stories of some College of Medicine students.

Most of my family is still in Korea; it’s just me and my brother who are in the States for school. I first came over to the U.S. for high school, and because I lived most of my life in Korea before then, it was undoubtedly a huge transition. Differences in culture, language and even food were all very difficult to overcome. There were many times that I wondered if leaving my family to study in another country was the right thing to do. Homesickness was a real issue in the beginning, especially when I was younger. But ultimately, I do think it was the right decision, as I’ve met so many wonderful people here and experienced many opportunities I would not have if I stayed in Korea. Still, I miss my family and my hometown and will make an effort not to lose sight of my origins. I would like the chance to visit Korea the next chance I get, maybe as a fourth-year. Until then, Facetiming and calling my family whenever I can will have to do.

Sage Gee, second-year medical student (2019-2020)

- Mom’s side: Landlords

- Dad’s side: Mongolian nobles

When I have conversations with others about my heritage, I noticed how people tend to clump the Asian Pacific immigrant stories under one umbrella, usually related to pursuing a graduate degree or getting hired in the U.S., when in fact, they are much more diverse. On the contrary, my parents’ immigrant story, and that of many Vietnamese immigrants, is that of political refuge. They sought to escape the Communist regime that took over their country, risking their lives to find a home and regain the basic rights that they lost. They came here with no money or possessions and knowing very little English, and they had to work full-time while studying to pay for their living expenses and get a degree. What got them through these tough times was their strong connections with their families. Family is a very high priority in Vietnamese culture, and on top of that, family provided a safe refuge for my parents as they navigated an unfamiliar world.

Giang Ha, third-year medical student (2019-2020)

I have always admired the resilience and determination that my parents faced to overcome the struggles that they experienced to get to where they are today, but at the same time, this resilience and determination also came with a strong sense of self-reliance. Seeking help from others was a sign of weakness, and this included mental health. I was raised with the idea that mental health services were unnecessary and that you should be able to overcome all anxieties, traumas and stress on your own. While I am someone who liked to express my emotions and talk about my problems, I find it difficult to talk to my family. This cultural stigma has played a significant impact on the Vietnamese-American community and, more generally, the AAPI community.

Despite the continual increase of mental health awareness and acceptance, we lag behind other populations in seeking mental health resources, and we are hesitant to express our struggles and instead deal with them on our own. I remember asking my father a few years ago which country he calls home, and, to my surprise, he said here, even though his culture and heritage was so different. Even though he was born and raised in Vietnam, he said that the Vietnam he would call him home was gone when North Vietnam won the Vietnam War. While they are appreciative of what the U.S. has provided them and me, in some ways, they also feel that they do not have a home where they truly belong. I also have shared these feelings to some degree. My parents have always immersed me in their own culture and values, and I always struggled in integrating and balancing the American culture in school and the outside community and the Vietnamese culture at home and with family. In witnessing and experiencing this identity crisis, rather than choose between Vietnamese and American, I have realized that maybe we just have our own unique identity, as a Vietnamese-American.

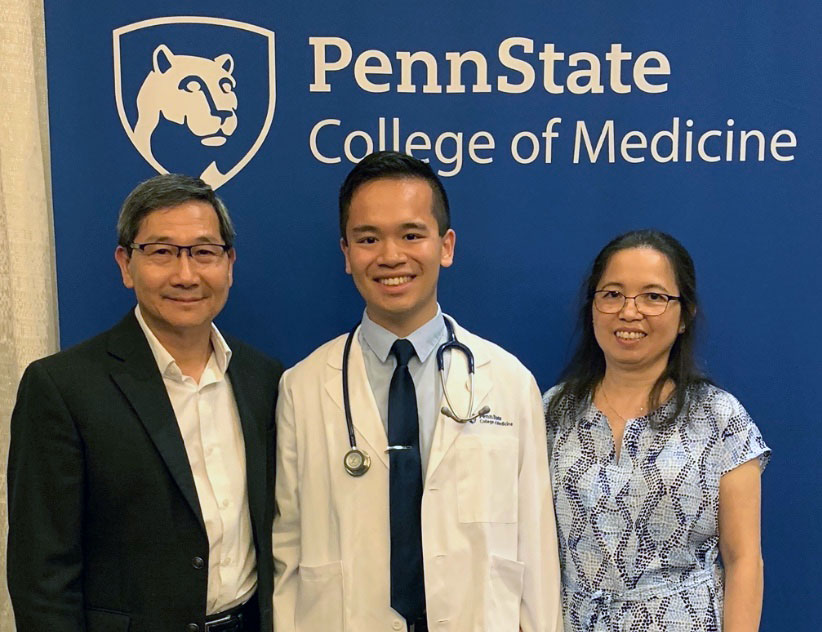

Don Hoang, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with his family

For my father, in particular, this meant leaving behind his entire family as he moved thousands of miles away to follow my mother.

Starting from scratch was definitely difficult, but, fortunately, my father would get the opportunity to attend college.

And, through hard work and perseverance, he would be able to find work as an engineer and eventually establish a comfortable life for himself, my mother, and me, granting me opportunities that no one in my family previously had. Now, while it has been many years since my family left Vietnam in search of a better life, my family still strongly embraces our heritage and the Vietnamese culture.

No matter what, Vietnamese culture is ingrained in our identity.

My family is from Korea and we still have deep-rooted ties to the Korean cultures and traditions. We come from a family of independence movement leaders, who fought for their life during the Japanese raid in the era of World War II for Korea’s independence. Our family takes pride in this and have our hearts deeply invested to our motherland. We still have many celebrations of Korean holidays and enjoy time with other members of the community to continue the tradition. This usually comes with amazing delicious food and a day of fun games and company. It’s sometimes difficult living in area where every else is so different, but that is what makes us unique and interesting. I’m proud of my heritage and Korean background and wish to spread knowledge about the Korean culture, tradition, food, entertainment, etc. to those who may not know yet.

Jungeun Jasmine Lee, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with her family

Ten years ago, when I decided to marry my husband, a Korean man, it was because I was fascinated by how different he is. I knew that being married to someone so different from me would be a lifelong challenge. Only after meeting and marrying him, did I begin to learn about the Korean culture and the history that explains much of it. My Korean also improved significantly from that of a 5-year-old to that of a fluent and bilingual adult. And communication with my parents has evolved tremendously, which allowed

me to learn about my family’s heritage. Both of my parents are the youngest of about five siblings each, with their oldest siblings being approximately 25 years older than them.

I’ve learned that a lot has happened very recently in the history of Korea. Japan colonized Korea for decades before the Korean War took place in the 1950’s,just years before my parents were born. My older uncles recall leaving their home, now part of North Korea, in my great-grandfather’s ships with dozens of other families. They moved several times, and each of my father’s siblings were born in very different areas of the country, before settling in Seoul, where my parents met. Since learning about the history and cultures of Korea, I’ve realized how much the country and its people are defined by its resilience and exceptional work ethic. My aunt recalls learning Japanese, from when Japan colonized Korea and attempted to rid the country of its native tongue. Less than 20 years after Japan left and the Korean War ended, my uncle went with thousands of other Korean men to fight in the Vietnam War.

Despite decades of colonization, war and extreme poverty, within just 50 years, Korea has grown into a powerful nation. Seoul is now one of the greatest cities in the world. Korea is known to have the fastest internet speeds and technological advances on par

or better than those in most other developed nations. Samsung, LG, and Hyundai are household names all over the world. Being Asian American is a struggle because many people in the States assume us to be non-American and, at first glance, deem us to be too different to interact or relate with. Every day, I meet people who stare at me then seem surprised when they hear me speak English. And the xenophobia seen during the COVID-19 pandemic only highlights the experiences Asian Americans have had for years. In addition, not only are we seen as “other” in the States, but when we meet Asians, they quickly realize that we are different from them and deem us as “other” as well.

The identity of an Asian American tends to be difficult to understand and the Asian American experience brings with it an opportunity to learn a lot about human nature, about different cultures, and about ourselves. Being bullied, ostracized and “other-ed” daily for my physical Asian features, and having difficulty understanding my parents, I grew up denying much of my Korean heritage. I avoided dressing “too Korean” or interacting with other Asian Americans and was careful not to speak Korean outside of the home. However, having had the opportunity to learn about the history and culture of Korea, and many of its strengths, I am learning to be proud of my heritage and proud to say that I am Korean American.

Chandat Phan, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with his family

Asian-Americans are often labeled as the “model minority” or the “over-represented minority”. These labels only serve to belittle the hard work and grit that many people of color must exhibit to overcome systemic racism that affects all people of color. These labels give an excuse for people to defend a failed system by pointing to success-in-the-face-of-adversity stories instead of recognizing the dire need to fix the system from the ground up. My hope for the future is to be part of a country that truly supports all people no matter their heritage or where they come from.

Hi, I wanted to share a poem with you all for APA Heritage month that I wrote about my grandma that got published in Mixed Life magazine. See Below 🙂

“Grandmother – Lost in Translation”

You say you are proud.

That I represent all of only your best qualities.

You speak to me from tomorrow (14 hours to be exact)

& I am still stuck in last night where I can only listen.

You see, I cannot speak my mother’s tongue,

I’ve lost our culture,

My son cannot even tell you that he loves you,

At most we can smile and nod our heads.

We know only to bow respectfully now.

Mom and Dad are from Karachi, Pakistan, moved here in 1994. Dad moved here to go through residency and moved to NYC.

My parents immigrated to America for many of the same reasons immigrants embark on this rite of passage: opportunity, economic prosperity, and a brighter future for themselves and their children. My cultural heritage lies in Punjab, India, which is colloquially known as the breadbasket of India. They come from humble beginnings where both were raised on farms in small villages. There were many factors that caused my parents to leave Punjab, especially socio-political reasons. In the 1980s, the Sikh-Punjabi community wanted to secede from India and form its own nation. This resulted in political rifts and eventually resulted in Operation Blue Star, a military operation governed by the prime minister of India that attacked the Golden Temple, a holy temple for Sikhs.

The event incited tremendous violence, torture, and trauma resulting in what felt to the Sikhs, a war against them. It became a place of fear for my family, one in which stepping outside could result in severe consequences. And to this day, the silence of the Sikh community, with regards to these events, echoes. My parents sought political refuge in America and immigrated in the l990’s. They came with essentially nothing: no wealth, no higher education, and no clear path to success. What they did have was an immigrant community to lean on. Through the help of the Sikh community in California, including extended family and friends, they worked in local gas stations and fast food restaurants, until they eventually opened up a Subway sandwich shop. They left behind a war-torn, politically fraught Punjab, along with their family, to scrape their way to something financially stable.

However, their struggles do not end there. Many of today’s struggles stem from the deep misunderstanding of my heritage: Sikh-Punjabi. Although Sikhism is the fifth largest religion in the world, many in America do not know who we are. Many may recognize a turbaned man, but not know that he is a Sikh man. After the events of 9/ll, hate crimes spiked against Sikhs because people thought we were Muslim, which in itself does not justify hate. For my parents, injustice did not end, refuge was not gained, and they remained in liminality. Punjab was unsafe and now America became unsafe. We have faced prejudice, discrimination, and adversity, but this is what makes Sikhs a stronger community. Our basic tenants are seva, selfless service, and dharam, justice and equality of humankind. Sikhs have always given back to their community, whether in Punjab or in America no matter the socio-political atmosphere. It is amazing to see the resilience of my community, one that I am so proud to be a part of. I think we as minorities need to advocate for our communities, give back -seva-to our communities give voice to the silenced, and uplift each other to seek the equality and equity – dharam – we deserve.

Melody Wang, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with her family

While the rest of the world uses the Gregorian calendar, Taiwan has its own separate Republic of China calendar to document the passing years. Also, we have amazing food! Boba or bubble tea originated from Taipei around the 1980s, and the famous soup dumpling place Din Tai Fung also originated in Taiwan. If you ever find yourself in the country, make sure to also try some pineapple cake, oyster pancakes and some stinky tofu!

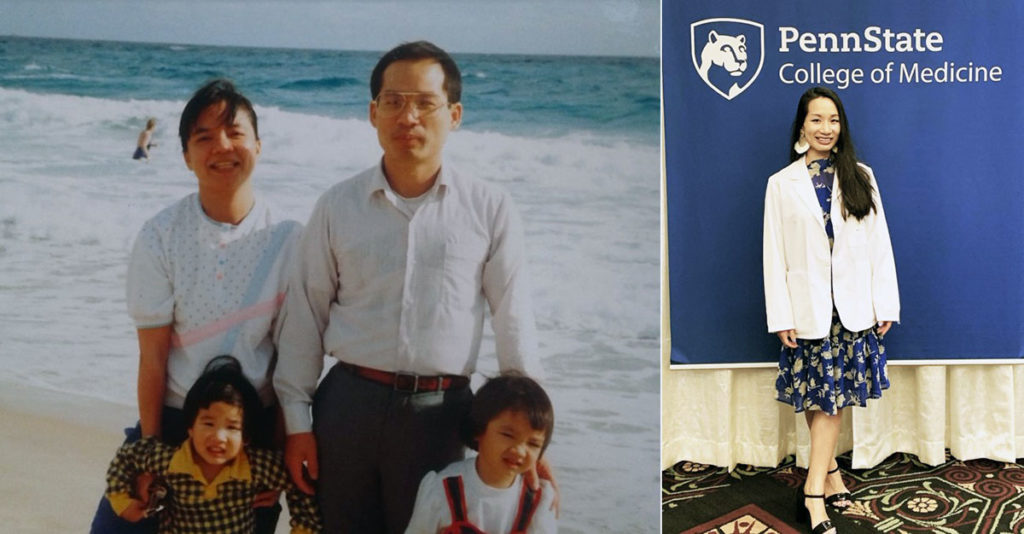

Alyssa Wang Tuan, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with her family (at left) and at the College of Medicine

It wasn’t until college that I learned more about what it meant to be an Asian American and about the wide diversity of Asian cultures that exist within this monolithic term. I really appreciate having this heritage and the sacrifices that my parents made, such as moving far away from their family and friends. I am glad to have two cultures that I can celebrate and be a part of. I

hope that my family’s future generations will understand their heritage and be able to take part in it in a meaningful way.

Ashley Wong, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with her family

My mother’s parents came to the U.S. under a “false” identity, and their papers had the surname “Toy.” They had 3 children, one of whom was my mother. I find it really interesting how my mother grew up with the last name “Toy” and was not allowed to change her surname back to her true last name “Jung” until high school. My mother grew up across the bay bridge in a town called Richmond, which was a very low-income area. She is very reserved when it comes to talking about her family because her mother, father, and sister all passed when she was in her late teens. My mother is constantly trying to replicate her mother’s Chinese cooking, and also tells me stories of how her mother tried to make American food and would make spaghetti with pasta and ketchup. All

in all, my parents both stem from lineages from the Canton region of China, but their family’s stories are completely different and somehow managed to cross paths. I may never come to fully understand the obstacles my family had to overcome to offer me the life I have today, but I am truly grateful. My parents were the first of their families to attend college, and I am the first of either family to attend higher education. I am thankful for all the sacrifices my family has made to offer me the opportunities I have today and ask you all to think about how you got to where you are today.

I am Chinese-American! I am not just Chinese, and I am not just American. I struggled to find which part of myself to identify with when I separated these two cultures, but really found my true identity when I appreciated how I am a combination of Chinese and American. This photo is me and my family visiting the village that my father’s ancestors left to come to America. The village is in Canton, China.

Jay Yang, second-year medical student (2019-2020), with his family

My parents immigrated to the U.S. from Shanghai, China, in 1989, a year after my brother was born. My dad came over first, and struggled to establish himself for a few months on his own before my mom followed suit. My parents tell me stories about the tough living conditions they experienced early on in their time in New Haven, Connecticut, and I am grateful for all they have endured to allow me to have the life I have today. One aspect of their life that stands out to me is the fact that they had to share a room the size of my bedroom today with 2 other families, and they all had to share a single bathroom! I always laugh at my mom when she tries to squeeze the last drop of toothpaste out of a tube for a whole week, or when she rinses a bowl of rice to make sure no grain goes to waste, but it’s also how they managed to make the most of what they had when they didn’t have nearly as much. After living in Connecticut for a few years, my family then relocated to New Jersey, moved once in New Jersey, then moved to Pennsylvania, and now, Kentucky. And somewhere along the way, I was born.